I wanted to share this paper I wrote last year about a show I saw at the Tate Britain; All too Human; Bacon Freud and Century of Painting. This paper is about me exploring future guides in the art world. The influences on my art have been dominated by men; El Greco, Velazquez, Goya, Van Gogh, Matisse, and the preeminent bad boy of the art world Picasso. Discussing women artists in post-war UK laid a new seed to be planted, offering a contrarian viewpoint on the gaze of the artist.

The All Too Human: Bacon, Freud And A Century of Painting Life exhibit at the Tate Britain gallery (February 28–Aug 27, 2018) is a panoply of British figurative painting from the 1900’s to the present. In post-war Britain, figurative painting was largely defined and driven by the School of London; a loose conglomeration of largely male artists: Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, David Hockney and others who through friendship and shared interest in their craft created a sphere of influence in the post-war London art world. The show is chronologically presented amongst multiple gallery rooms and is dominated by male artists who command over 80% of the exhibition. The women artists represented are few, but match their male counterparts: Celia Paul, Cecily Brown, Jenny Saville, and Lynette Yiadom-Boaky; though they are confined to the smallest gallery at the very end of the exhibit. Paula Rego is the only woman to have a gallery of her own, just preceding her fellow female artists.

While the influence of the male British figurative painters on the women artists is significant, the women presented in the exhibition found their own distinct styles in how they chose to represent women, women’s lives, and women’s bodies. From a feminist perspective, after centuries of male domination of the depiction of women’s bodies, the re-appropriation of the female body by women artists in a patriarchal society was and continues to be an act of rebellion. The female nude has been elevated into the canon of Western art as one of the defining pillars of art, but the female body has been almost exclusively defined by male artists. The All too Human exhibition captures and reflects this divide between the male and female portrayal of women and their bodies. The exhibition’s post-war works provide strong, contemporaneous examples of both portrayals that when viewed in close proximity accentuate this divide.

After World War II, amidst the dominance of the Abstract Expressionists in the United States, the figurative painter in Britain, primarily in London, experienced a resurgence, but continued to be almost the exclusive realm of men. Sir William Coldstream was a prominent artist during the post-war period, but it was his role as a teacher and director of the influential Slade School of Art (1949-75), and his involvement in other civil and pedagogical institutions, where his influence was most profound and reverberated for decades. His own immersion in figure work, which began after he returned from World War II, was reflective of an existential understanding of life.

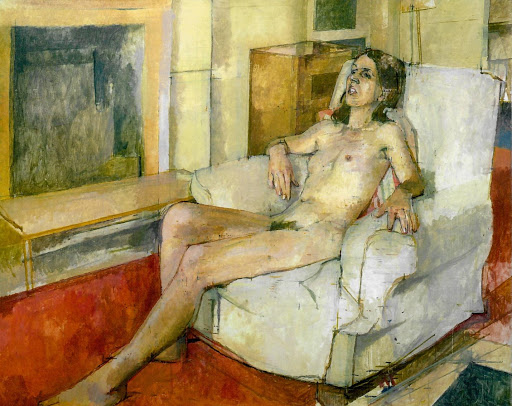

In the exhibition, Coldstream’s Seated Nude (1952-3, figure 1) portrays a female figure seated alone with the lines of his extremely careful measurement still visible. The painting’s limited earth toned palette, the ghosts of the lines, and the vacant look of the woman all feel like scars of war.

In his other Seated Nude (1973-4, figure 2), a colorful interior houses the subject. Although younger and separated by decades, she too has a vacant, distant stare. “The critic David Sylvester suggested that Coldstream’s process of measuring to establish the exact position of the model in relation to the painter was governed by existential ideas of ‘apartness’ and an ‘unremitting’ insistence on the otherness of other beings and things.” Intense scrutiny was central to the process of making paint real and alive.

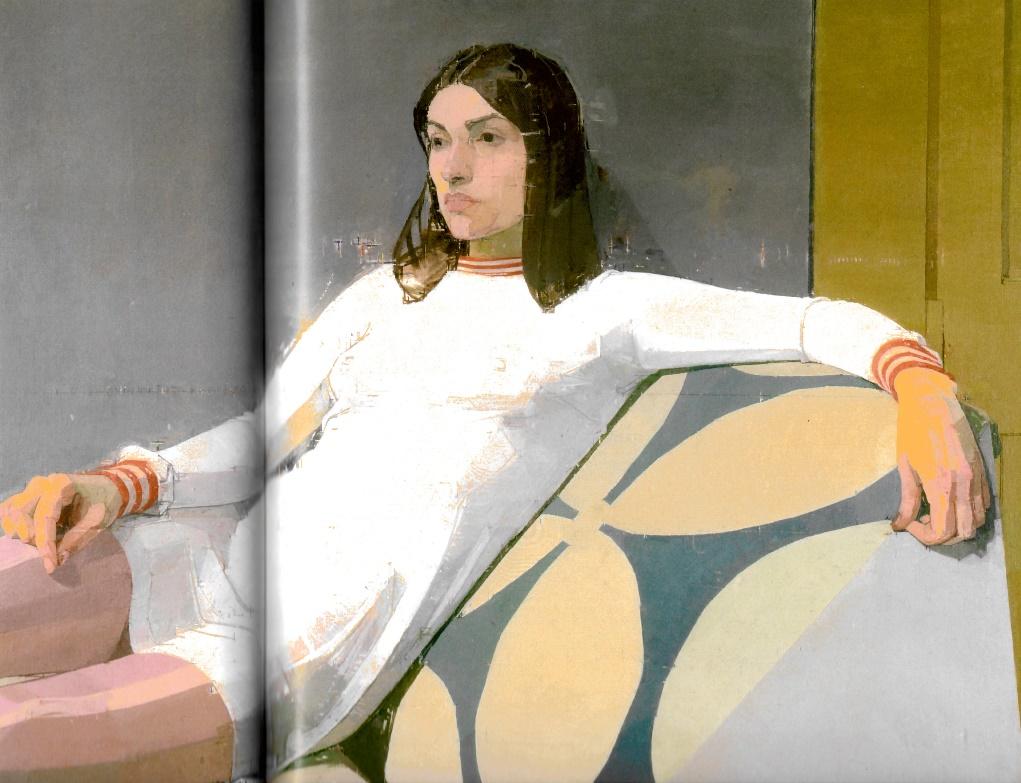

Coldstream’s impact on other painters is captured in the exhibition in the works of Euan Uglow and Lucian Freud. Uglow was a student and Freud a tutor at the Slade, and both were influenced by Coldstream’s attention to strict scrutiny of the model. Uglow’s piece in the exhibition, Woman with White Skirt (1953-54, figure 3), appears strikingly similar to Coldstream’s Seated Nude (’52-3), except that the earth tones are sculpted more to give the impression of flesh. In both Uglow’s and Coldstream’s work, the model is an object that the artist brandishes his control over. This theme is continued in Uglow’s Georgia (1973, figure 4), where close observation reveals the carefully drawn measurement lines. Uglow’s control is so exact he insisted on how the model’s hair was cut and the precise clothes she would wear. The model drew the line on taking her clothes off and was at least allowed to keep her name.

Francis Newton Souza (1929-2002), like Bacon, Freud, and Rego in the exhibition, has an entire room dedicated to his work. Souza was an Indian expatriate painter active in London (though largely eclipsed by the School of London) from the mid 1950’s until the mid 1960’s when he moved to New York. Raised in a pious Catholic home Souza who was expected to be a priest before he was expelled from Catholic school for drawing pornography on the walls. He would later say he was descendant of the Dadaists and the devil. Catholicism, and his rebellion against it, heavily influenced his work.

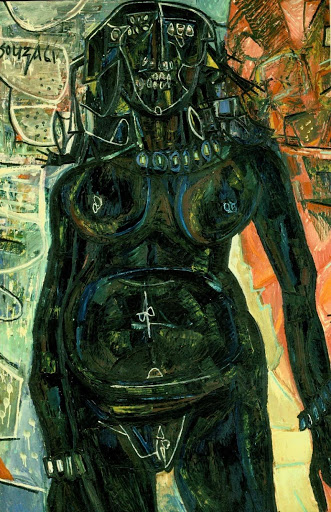

As one walks into the gallery where Souza’s paintings are hung, one is immediately gripped by the abstract expressionistic force and action contained in the Black Nude (1961, figure 5). The Black Nude is a monstrous, prodigious, three-quarter representation of a figure: part woman, part beast, part other worldly being, painted in bold strokes of black, brown, yellow, and blue. The background is an abstract surface of circular lines and geometric shapes in a cacophony of primary colors. White lines create a mask of baring teeth over a face which is neither recognizable as male nor female. Blue lines voluptuously carve out her breasts and large abdomen. Her genitals, drawn in white, protrude more like a penis than a vagina. Though standing, the view is one of which she would have to be laying down with her legs opened. This arresting sexualized, almost violent creature is not a life-giving, loving portrayal of women, but one which is sexually disturbing and threatening. Souza signs his name on the left side of her head as to say he created her, he is her master, and he controls her.

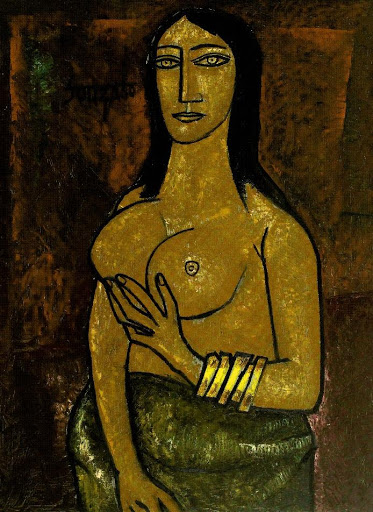

The female figure is predominant in Souza’s body of work. Women in Souza’s paintings are either whores or saints. Hanging on the wall adjacent to Black Nude are Souza’s Nude Holding Breasts (1960, figure 6) and Two Saints in a Landscape (1961, figure 7), which both exude docility in painting style, palette, and temperament. The females, both look exactly the same even though one is a saint. They are doe-eyed, docile, large-breasted caricatures of women like the Black Nude , but everything about them is smooth and gentle while the Black Nude is jagged and brutal. Both forms are one-dimensional projections of Souza’s limited projections of complex, independent beings.

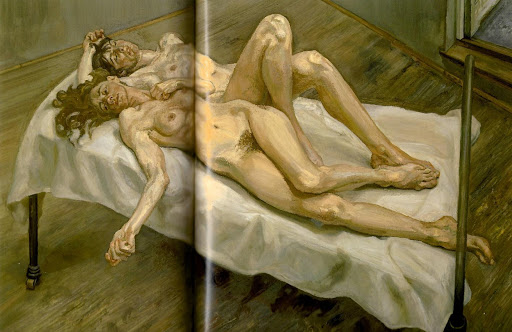

Lucian Feud (1922-2011) has the most dominant presence after Francis Bacon in All Too Human (interestingly, Bacon does not have any work depicting women in this exhibit). Freud, throughout his painting career, has worked solely and entirely from life; only with models close to him, and with those whom he knew well. Lucian Freud, like Coldstream and Uglow, relied on fierce, removed, observation, but rather than attention to exact measurement it is the corporeality of the skin which was primary to Freud. Freud’s work in both portraiture and figure is often described as hardened and uncompromisingly honest. Freud describes his process thus: “I’m not trying to make the copy of the person. I’m trying to relay something of who they are as a physical and emotional presence. I want the paint to work as flesh does.”

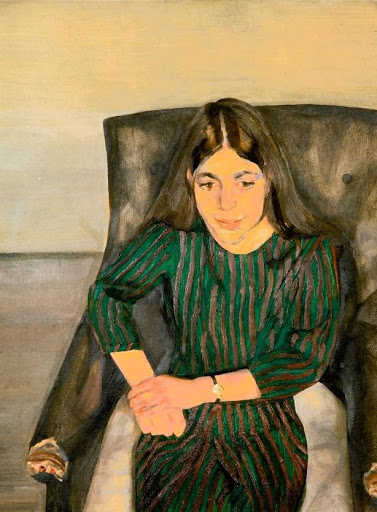

‘The paint working as flesh’ which captures the rawness of humans’ animal being is a signature element in Freud’s paintings. There is a tenderness in the portraits of his daughter Annabel (1967, figure 8) and of Celia Paul in Girl in a Striped Nightshirt (1983-5, figure 9), but the nudes exude a different quality.

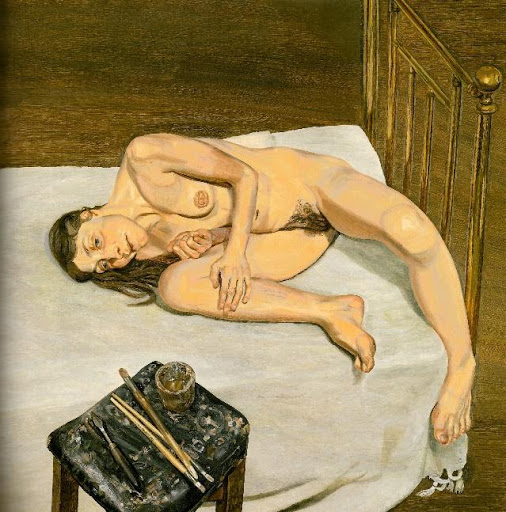

In Naked Portrait (1972-3, figure 10) of Jacquetta Elliot, with whom Freud had a decade long love affair, she appears like a wounded animal in a semi-fetal position, with one fist clenched to her chest and one leg draped down revealing her genitalia at the end of a brass barred bed. Although Jacquetta is entrancingly beautiful, Freud mercilessly strips away her beauty. Her piercing blue eyes plead helplessly and haunt the viewer. This is a powerful portrayal of a woman who has no power. The feeling of desperation and sadness are palatable. The paint brushes and palette knife on the table in the foreground lurk on the side of her like her instruments of torture. Sleeping by the Lion Carpet (1995-96, figure 11) contains a different immediacy.

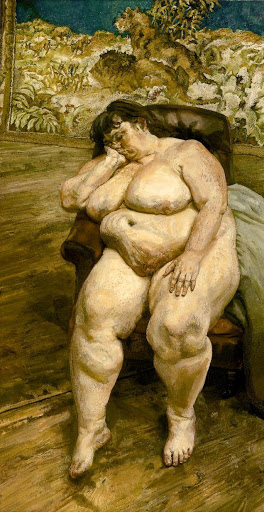

This painting of a massively overweight Sue Tilley, asleep below the waiting lions, further encapsulates Freud’s emphasis on the human as animal. Tilley as a person here is insignificant. It is the folds of flesh under the unwavering, unflattering gaze of the painter which have worth and consequence in Freud’s world.

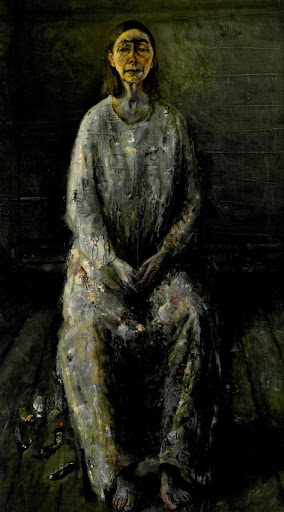

The significant women artists in All Too Human do not appear until 1980 with Dame Paula Rego (b.1935) whose work is rarely seen. Rego is a Portuguese expatriate who came as an adolescent to London to study art and was a student of Coldstream’s at the Slade. When one enters Rego’s gallery the women-as-objects zeitgeist of the male-dominated All Too Human exhibit begins to metamorphize and transform. The world of women comes clearly into focus with her large, complicated narratives revealing complex relationships between men and women. The Coldstream influence is seen in Rego’s carefully composed figures done in pastels contained within the lines. However, she departs from her teacher in the complexity of the stories she tells. Rego’s work prior to 1980, done in Portugal, was largely politically motivated; however, with the death of Rego’s husband from multiple sclerosis, her work experienced a fundamental change, becoming introspective and personal. Shadows appear for the first time.

The Family (1988, figure 12) has the feel of a dark fairy tale, telling the duplicitous, multi-dimensional story of caring for someone who is ill. The female shadows have a strong presence. The man, helpless, is dressed by his wife and children. Reflecting the raw emotions in life, there is a whole gamut of emotions which lack in Rego’s male counterparts in exhbition. As noted in the All Too Human exhibition catalogue, “Rego’s female protagonists do not conform to the idealized female characters of canonical art history; they are multifaceted and human.”

Confined to the last room, the enormity and power of the women’s work feels as if it will break out of the walls. The first painting we see is a self- portrait of Celia Paul, Painter and Model (2012, figure 13). Paul is a direct descendent of previous generations of figurative painters such as Chaim Soutine (early twentieth century painter included in the show) and Lucien Freud. Celia Paul was Lucien Freud’s student and lover for several years; his influence making a substantial, long-lasting imprint on the young painter. Freud’s subdued, earth-toned palette is similar to Paul’s, as well as the emphasis on thick layers of paint with obvious prominent brush strokes. Like Rego, Celia Paul’s work is about relationships, but like her mentor and paramour, Paul only paints those close to her.

In Family Group (1984-85, figure 14) Celia Paul’s painting of her family exudes familial warmth, and comfort. Celia Paul deviates from Freud in her empathy toward her sitter, or sitters. Hattie Spires, assistant curator of All Too Human elucidates: “Unlike Freud’s unflinching approach that scrutinizes his subjects with an unsentimental objectivity and the all-encompassing gaze that pays as much attention to the surrounding environment of the studio as to the sitter, Paul’s intimate, quiet portraits bring their inner life to the surface.” In Girl in a Striped Nightshirt (1983-85) the fascinating painting relationship between Freud and Paul is captured as Freud produces a tender serenity, seemingly true to Paul’s nature; a sensitivity rarely seen in Freud’s work. However, the authenticity of that tender moment comes into question when the focus shifts to the nightshirt. The nightshirt worn by Paul is disturbingly reminiscent of the striped uniforms or “striped pajamas” worn by prisoners in Nazi concentration camps.

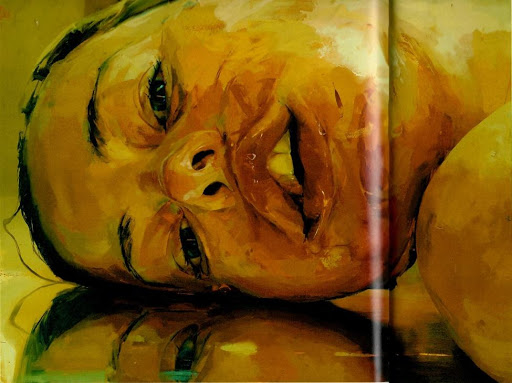

Creating an intriguing juxtaposition to Celia Paul’s quiet understated work on the adjacent wall is Jenny Saville’s Reverse (2003, figure 15). Reverse is an enormous, disarming, self-portrait engulfing the entire wall at 7ft x 8ft. The zoomed in view of Saville’s horizontally resting head and shoulder partially reflected in a mirror is bloodied, wounded, and defeated; yet, not hiding—she watches us with three eyes. Jenny Saville (1970), a British artist that made her debut in 1992 as part of the Young British Artists, radically broadens the definition of what constitutes female beauty by painting female nudes of varying degrees of sizes, sexual orientations, distortions, and deformities. Saville has been criticized for how she portrays women’s bodies. Catherine Milner laments the work is, “cruel, intense, fetishistic, loveless, unforgiving, and extremely shocking.” Meanwhile followers, enthusiasts, and ordinary women have thanked her for celebrating their full bodied, ordinarily shamed upon bodies. Saville uses a variety of materials, including photographs and medical journals. Saville spent time witnessing plastic surgery, and the evidence of that experience manifests in how she manipulates the paint to feel and look like flesh. She paints in deliberate slabs with sweeping strokes. Rejecting traditional skin tones, she paints with an abstract expressionist urgency and explosiveness in a fiery palette. Her use of oil paint, an organic, living substance brings a rawness to the paint. Saville often models for her own work as a sincere form of reasserting control of the actual physical body, as well as how the body is portrayed. Saville is influenced and compared to Lucian Freud, but while her painting style exudes the visceral and primal qualities of Freud’s paintings, she is more conceptual: “Saville is at heart a conceptual artist, whereas Freud is a traditional painter trying to make it look as though he has a concept.”

Saville’s Reverse centers on an agape mouth that is swollen and shimmering with blood. The mouth is delivered vertically. Saville’s disorientation of the face with the bloody mouth evokes an engorged vagina. Blood is very much part of a woman’s existence for several decades of her life, yet menstruation is seen as a “curse”, and something which brings shame. Here the blood is prominent, and although it could be interpreted that she was hit, that’s not clear. The curator’s choice of this painting is poignant because it has undertones of Chaim Soutine’s The ButcherStall (1919), an influence of Saville included in the show. Reverse is not a narrative painting, rather it is an intense moment in a woman’s life. It captures your attention as other large paintings, but it is not cluttered. Her gaze is piercing and discomforting. This is a real woman looking at you; though vulnerable, centered in her own power, unlike the wounded creature in Freud’s Naked Portrait. “The power of her brilliant and relentless embodiment of our worst anxieties about our own corporeality and gender is what distinguishes Saville from other paint-obsessed representers of the naked human body. To my eye, no other artist in recent memory has combined empathy and distance with such visual and emotional impact.”

Transversely from Saville in the final room of women, adjacent to Paul’s Family Group, lying in wait is a secret world of seduction in Cecily Brown’s Teenage Wildlife (2003, figure 16). Cecily Brown (b. 1969) came of age as a painter and graduated from the Slade in the early 90’s when figurative art and oil painting was of little relevance. Further obscured by the flash and blinding neon aura of the Young British Artists clique to which she did not fit in, Brown absconded to New York where the audience was more receptive. Brown’s work, a mix of abstraction and realism is lush, sexual, and firmly grounded in the figurative. Teenage wildlife is a verdant, fertile landscape which entwined within are two figures making love; enveloped in one another. One figure is a woman, but it is unclear whether the other figure is male or female. The androgynous figure is still clothed as if to make a quick escape if the young lovers are discovered. The pink/red tones of the flesh balance with its complimentary green as if the colors are also making love.

There is beauty and life dancing on the canvas; the opposite of a Freud’s subdued palette painting Two Women (1992, figure 17) of two naked female models. In Two Women the models lay along each other; one woman asleep, the other looking half-gazed with a clenched fist held to her heart. The only intimacy—touching feet. The sheets are also flesh colored, disheveled as if to suggest the two had been engaged sexually. The passion and lustiness in Brown’s work is absent here. Rather than a fulfilled couple they seem as if they are on a doctor’s examing table undergoing a procedure; they are.

On the last wall before leaving the gallery is the work of the youngest artist and only woman of color: Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (1977). Boakye paints people of color from imagination, emphasizing experimentation and working quickly with intention to create a moment. The titles of Boakye’s paintings are perplexing and mystifying; being works in themselves the titles do not necessarily relate to the work. Boakye understands the power of words. Manet, Sickert, and Degas are among the patriarch painters influencing Boakye. In The Host Over the Barrel (2014, figure 18) all three painters are present. Three dancers stand resolute, two with their backs to the viewer, one standing profile. All three watch something off canvas amidst a netherworld of various tones of green. Souza’s Black Nude is in sharp contrast to Hostover a Barrel. Black nude is a beastly view of a woman while Boakye’s women are self- possessed and confident, not caricatures.

Postwar London and its people were beleaguered, yet its painters continued to paint with passion and focus. Painting from the figure and from life did not lose relevance as it had in the United States with the ascension of the Abstract Expressionists. The existential anxiety associated with trauma and suffering that pervaded The London School of painters drove their pursuit of meaning and value in painting “Life.” Women painters will later learn from their male predecessors’ technique and styles, but they fundamentally change the way women and their bodies would be painted; women became less objects and commanded an independent presence. By controlling their own and their sisters’ images the women reclaim from men the power of the “gaze” in the All Too Human; Bacon, Freud, and a Century of Painting.

Literature

- Lynda Nead, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality, (London: Routledge, 1992), 3.

- Emma Chambers, “William Coldstream and the Slade” In All too Human: Bacon,Freud, and a Century of Painting, edited by Elena Crippa. 105-117. London: Tate Publishing, 2018.

- Gita Kapur, “Francis Newton Souza: Devil in the Flesh,” Third Text, volume 3, no. 8/9, 1989: 25-64.

- Laura Castagnini, “Lucian Freud,”In All Too Human: Bacon Freud, and A Century of Painting, edited by Elena Crippa. 145-161. London: Tate publishing, 2018.

- Auping, Michael, “Lucian Freud, in Conversation with Michael Auping,” May 7, 2009, in Sara Howgate, Michael Auping and John Richardon, edc. Lucian Freud: Portraits, London, 2012: 209.

- “ALL TOO HUMAN: BACON, FREUD AND A CENTURY OF PAINTING LIFE,” Tate Gallery, accessed March-May, 2017, http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/all-too-human.

- Katie Cambell, “Paula Rego.” In All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting, ed. Elena Crippa (London: Tate Publishing, 2018), 186-193.

- Hattie Spires, “Identity, Self, & Representation,” In All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting, ed. Elena Crippa (London: Tate Publishing, 2018), 194-204.

- Michelle Meagher, “Jenny Saville and a Feminist Aesthetics of Disgust,” Women, Art, and Aesthetics, vol 18, no. 4 (Autumn-Winter 2003): 23-41.

- Linda Nochlin, “Jenny Saville: Floating in Gender Nirvana,” Art In America, (March 2000): 234.

- Laura Castagnini, “Lucian Freud” In All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting, ed. Elena Crippa (London: Tate Publishing, 2018), 144-161.

- Rachel Cooke,. “Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: artist in search of the mystery figure,” The Guardian, (May 31, 2015).